Local, single-user, linear workflow#

Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG)#

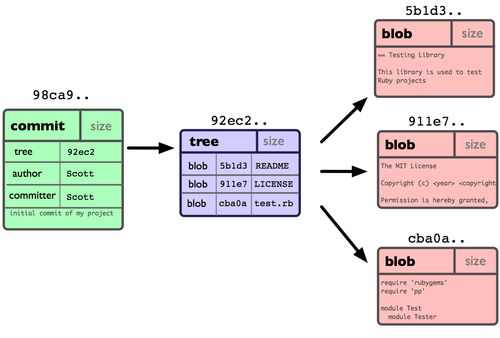

The fundamental unit of information in git is what is called a commit. A commit is a snapshot of a work at a point in time. Now, for version control systems we don’t want to have just one snapshot of our work, but instead we want many of them. Furthermore, instead of a linear sequence of snapshots we may imagine having multiple lines or branches of snapshots including different versions of our project. These commits are then organized in a directed acyclic graph, as the one shown in the following picture.

Credit: ProGit book, by Scott Chacon, CC License.

We identify each node (commit) with a hash, a fingerprint of the content of each commit and its parent. It is important the fact that the hash include information of the parent node, since this allow us to keep the check the structural consistency of the DAG.

Let’s create a first hash:

from hashlib import sha1

# Our first commit

data1 = b'This is the start of my paper.'

meta1 = b'date: 1/1/17'

hash1 = sha1(data1 + meta1).hexdigest( )

print('Hash:', hash1)

Hash: 3b32905baabd5ff22b3832c892078f78f5e5bd3b

Every small change we make on the previous text with result in a full change of the associated hash code. Notice also how in the next hash we have included the information of the parent node.

data2 = b'Some more text in my paper...'

meta2 = b'date: 1/2/1'

# Note we add the parent hash here!

hash2 = sha1(data2 + meta2 + hash1.encode()).hexdigest()

print('Hash:', hash2)

Hash: 1c12d2aad51d5fc33e5b83a03b8787dfadde92a4

Locals#

Type git to see a full list of all the core commands. We’ll now go through most of these via small practical exercises:

!git

usage: git [-v | --version] [-h | --help] [-C <path>] [-c <name>=<value>]

[--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path] [--man-path] [--info-path]

[-p | --paginate | -P | --no-pager] [--no-replace-objects] [--bare]

[--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>] [--namespace=<name>]

[--super-prefix=<path>] [--config-env=<name>=<envvar>]

<command> [<args>]

These are common Git commands used in various situations:

start a working area (see also: git help tutorial)

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

work on the current change (see also: git help everyday)

add Add file contents to the index

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

restore Restore working tree files

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

examine the history and state (see also: git help revisions)

bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

grep Print lines matching a pattern

log Show commit logs

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

grow, mark and tweak your common history

branch List, create, or delete branches

commit Record changes to the repository

merge Join two or more development histories together

rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

switch Switch branches

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

collaborate (see also: git help workflows)

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

'git help -a' and 'git help -g' list available subcommands and some

concept guides. See 'git help <command>' or 'git help <concept>'

to read about a specific subcommand or concept.

See 'git help git' for an overview of the system.

Tip

You can execute commands in bash from a Jupyter notebook by adding the ! in front. You can also add the magic %%bash at the top of the cell to indicate that all the code in the cell must be executed in the shell.

Warning

If well you can do most of the following git operations from a notebook, we actually recommend you to execute this commands directly from the shell.

First we create an empty folder and then we initialize it as a git repository. From your terminal, run

git init test

Let’s see what git just did. Move inside to this folder and use the listing function to show all the files and directories inside the test repository test:

cd test

ls -la

Note

What makes test a repository? If you pay attention to what is inside the folder, you will see an especial folder called .git. Here is where all the information that git is using to version control your files belongs. If you delete this folder, then your repository will pass to be a simple folder with no version control capabilities.

Now let’s edit our first file in the test directory with a text editor. We can also create a new text file with the next command.

echo "My first bit of text" > file1.txt

The first step we have to do in order to version control this new file, we need to add it

git add file1.txt

We can now ask git about what happened with status:

git status

The next step is to commit our changes to permanently record our changes in git’s database. For now, we are always going to call git commit either with the -a option or with specific filenames (git commit file1 file2...). This delays the discussion of an aspect of git called the index (often referred to also as the staging area) that we will cover later. Most everyday work in regular scientific practice doesn’t require understanding the extra moving parts that the index involves, so on a first round we’ll bypass it. Later on we will discuss how to use it to achieve more fine-grained control of what and how git records our actions.

git commit -a -m"This is our first commit"

In the commit above, we used the -m flag to specify a message at the command line. If we don’t do that, git will open the editor we specified in our configuration above and require that we enter a message. By default, git refuses to record changes that don’t have a message to go along with them (though you can obviously ‘cheat’ by using an empty or meaningless string: git only tries to facilitate best practices, it’s not your nanny).

Tip

You can use git log to see what has been commited so far

git log

Sometimes it’s handy to see a very summarized version of the log:

git log --oneline --topo-order --graph

Git supports aliases: new names given to command combinations. Let’s make this handy shortlog an alias, so we only have to type git slog and see this compact log:

git config --global alias.slog "log --oneline --topo-order --graph"

and now we can use this new alias to print a short version of the commit history

git slog

Let’s do a little bit more work… Again, in practice you’ll be editing the files by hand, here we do it via shell commands for the sake of automation (and therefore the reproducibility of this tutorial!)

echo "And now some more text..." >> file1.txt

And now we ask git what is different

git diff

The format of the output above is well explained in detail in this Stack Overflow post. But we can provide a brief summary here:

diff --git a/file1.txt b/file1.txt

This tells us which files changed overall, with ‘a’ representing the old path and ‘b’ the new one (in this case it’s the same file, though if a file had been renamed it would be different).

index ce645c7..4baa979 100644

These are hashes of the file at the two stages, needed by git itself for other operations with the diff output.

The next block shows the actual changes. The first two lines show which paths are being compared (in this case the same file, file1.txt):

--- a/file1.txt

+++ b/file1.txt

The next line indicates where the changes happened. The format is @@ from-file-range to-file-range @@, where there’s one more @ character than there’s parents to the file comparison (git can handle multi-way diff/merges), adn the file range format is -/+<start line>,<# of lines>, with - for the from-file and + for the to-file:

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

Lines prepended with - correspond to deletions (none in this case), and lines with + to additions. A few lines around deletions/additions are shown for context:

My first bit of text

+And now some more text...

And for now on, the circle of virtue just repeats: work, commit, work, commit

git commit -a -m"I have made great progress on this critical matter."

While git add is used to add files to the list git tracks, we must also tell it if we want their names to change or for it to stop tracking them. In familiar Unix fashion, the mv and rm git commands do precisely this:

git mv file1.txt file-newname.txt

git status

Note that these changes must be committed too, to become permanent! In git’s world, until something hasn’t been committed, it isn’t permanently recorded anywhere.

Apendix#

These is the sequence of all bash commands we have use in this tutorial in the right order.

git init test

...

...

...